What the history of welfare in America can teach us about the stigma surrounding government help

There's a little known slice of American history that has to do with President Richard Nixon, the East Room of the White House, and country music singer Johnny Cash.

In 1970, Nixon asked Cash to come to the White House and perform for his "Evening at the White House" Concert series, as his key advisors saw this as a way to woo Southern voters and appeal to so-called 'classic American values'.

Nixon requested Guy Drake's Welfare Cadillac, a song that uses folksy punchlines to disparage welfare recipients, painting a picture of a man in poverty who abuses the system by using his paychecks to buy a new Cadillac car. In it lives the most famous and time-honoured myth of the American welfare system: that its participants are lazy, fraudulent, and somehow living a life of luxury on the government dime. To understand the power this image has had in shaping the national debate surrounding welfare, it's important to recognise the ways in which American individualism and systemic racism intersect.

* * *

Professor Joe Soss specialises in both social welfare policy and income inequality, among other things, at the University of Minnesota's Humphrey School of Public Affairs. “Generally there tends to be pretty low factual knowledge regarding the average American's understanding of the welfare system," Soss says, "and when people are given facts that contradict their beliefs about welfare, they tend to reject those facts in favour of retaining their beliefs."

So, if not fact, what is the genesis of these public perceptions? Soss argues that true understanding has to go deeper than the words we use. While certain phrases may frame the debate, like "handout" or "welfare queen"—a derogatory label hoisted on female benefit recipients by politicians in the 1970s—the fundamental ideas behind the terminology represent much older and more durable prejudices.

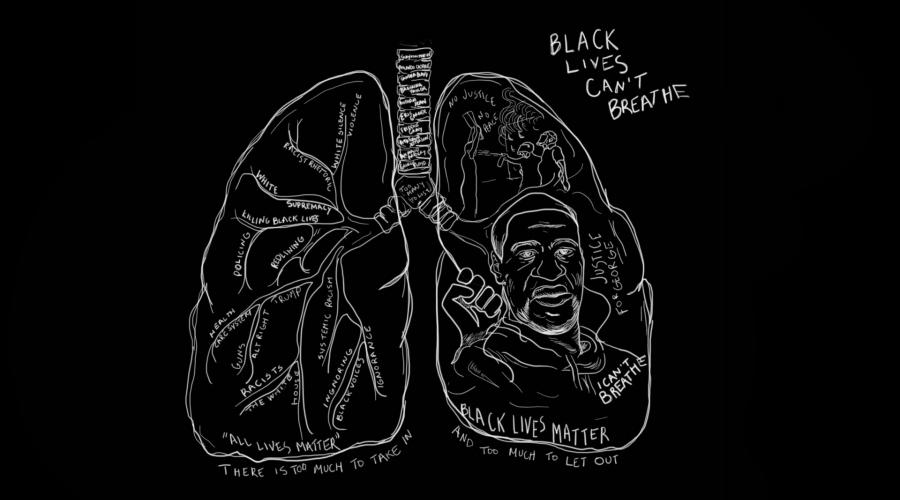

"Take the word 'welfare' for example," Soss explains, "the word is powerful in its evocation, but it's important to understand that what is being evoked is a set of stereotypes about people who are poor and stereotypes rooted in racism that long predated the term welfare as it's been used since the 1960s." The notion that poverty is a symptom of race and not in fact of racism has always been a heavily favoured narrative in American society. Welfare, Soss argues, merely concentrated these well-worn prejudices into a system and made them visible enough to power a national debate.

Anne Price, the President of the Insight Center for Community Economic Development, has spent over 30 years working on welfare and says that these narratives have a lot of money and political might behind them.

"The idea of deservedness is deeply embedded in our psyche and in our messages," Price says. "Part of that is predicated by neo-liberalism and the idea that it’s really up to individuals to make their way."

In keeping with this, the US had essentially no social safety net until the Social Security Act of 1935 was passed, which allocated public funds for retirement and unemployment insurance. Peter Edelman, a prominent American lawyer and policy-maker who specialises in poverty and welfare, said that with the shift, “the elderly had become deserving. They weren’t before that, nobody was before that.”

Edelman made waves in the mid-1990s when he stepped down from his position as Assistant Secretary of Health and Human Services for President Bill Clinton after Clinton signed The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act of 1996. The passage of this bill effectively created a hole at the bottom of the social safety net by putting a time-cap on benefits and tying them inextricably to work requirements. Edelman asserts that this slashed the number of Americans eligible for government help and failed in its mission to depoliticise the issue.

The "new Democratic Party" of Bill Clinton saw it as politically dangerous to be tagged as sympathetic to welfare given the attitudes of White working-class voters at that time. The drive to reform welfare into a new system that was based on incentivising work was meant to make anti-poverty programs more palatable to the highly individualised culture of the American electorate. This approach ended up backfiring, as public attitude shifted very little.

Soss co-authored a paper in 2007 with Professor Sanford F. Schram of Hunter College which found that "welfare retained negative connotations for large segments of the public in the post-reform era: it remained associated with dependence, laziness, and aid to Blacks." The final point in that list is perhaps the most key in dissecting the stigma that persists despite some policy shift. "A lot of my colleagues want to see this in economic terms," Schram says, "but really it’s racial terms.”

While the issue is connected to both class and race, Price argues that informed citizens have to go deeper when looking at low-wage jobs. The bloc of people pushed by the system into those jobs is completely "gendered and racialised," Price says.

“You need to understand this as a heavy-duty, race-connected system,” Edelman weighs in. “When Reagan talked about the "welfare queen", everyone knew that was a Black woman, we don’t want to kid each other.” Having been in politics for a long time, Edelman can trace it back to when candidates could no longer use the n-word publicly in their campaigns, saying they merely re-disguised their racism by supporting mass incarceration and bashing welfare, dog-whistle tactics meant to indulge their White base. "How our welfare system is weaponised is racial,” Price warns.

Professor Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, who studies the politics of the diminishing welfare state at Cornell University, asserts that the factors promoting stigmatisation are not just external; they are deeply embedded in the design of the system itself. Social security, she says, was constructed in a manner resistant to stigma. There was no one entering your home to check whether you were being a "good old person", deserving of your benefits. With the Aid to Families with Dependent Children program, however, which was in effect from 1935 to 1997, the relationship between government and recipient had a completely different tone. Local welfare officials could, for decades, visit unannounced, sometimes in the middle of the night, and use “suitable homes” or “men in the house” rules to deny benefits to women they deemed immoral or undeserving, Kohler-Hausmann explains. The money was conditional.

"Welfare shows that programs that are pitched as serving those that are 'not deserving' can easily be mobilised to stoke the social anxieties of the moment," Kohler-Hausmann explains. The image of the welfare queen is associated with a part of the cash assistance program that no longer even exists, but because it was, as Kohler-Hausmann points out, "a fertile political symbol", politicians were able to use its enduring legacy as a successful battering ram against all anti-poverty legislation. The irony of this, she says, is that we are all the beneficiaries of government aid. Tax cuts are a form of welfare, so are mortgage interest deductions—money uncollected is money spent—but because some recipients consider it to be their money merely being returned, the parallel goes unnoticed.

In academic circles, this idea is called the submerged state. “There's a lot of things in the US about the structure of our institutions and policies that makes it possible for people who are in the middle class and above to falsely imagine that they’re being victimised," Soss says, "that there's these generous things going to those people who are poor and unemployed.”

"It’s really insidious the way it works," Schram agrees, "deeply embedded in our discourse about welfare is who earned their benefits and who didn’t, and it's highly racialised. The people who get compensation, the people who earned their benefits who are deserving are overwhelmingly White, and the people who get welfare are not."

So, contextualising the money on a personal level won't do much good in reducing stigma, all four experts argue. One can easily justify their own circumstances while failing to extend that understanding to others. In the case of stimulus checks and unemployment insurance during the coronavirus pandemic, for example, little stigma has been attached since people do not feel that they are to blame.

Kohler-Hausmann has no trouble acknowledging that the pandemic does create "a common cause in this misery", but predicts it will not remove the public shaming associated with the welfare debate. Edelman agrees, explaining how when the Great Recession came on in 2009, he thought “all these middle-class people will say oh well it’s good to have this [welfare benefits] here because it was helpful for me so let's do more of it.” That powerful individualism persisted, however, and the American public remained reluctant to open their purse strings. "The answer was [that] they thought it was good for them because they deserved it, because they worked all their lives," Edelman explained, "and anyone who wasn’t working before the Great Recession was useless."

Those are the keywords: because they deserved it. Both Schramm and Soss cited the ‘American Dream’ and the glorification of Western liberal individualism as factors in the public calculation of deservingness. But, ultimately, they argued that race was more powerful a force than either of those.

"This deep-seated narrative is really built on the slave-trope," Price affirmed, "it’s so foundational."

The true work of dismantling the stigma surrounding welfare is the work of dismantling racist thought systems. Government aid can be a great leveller. It can step in and catch the most vulnerable who have slipped—or been forced—through the holes in the social safety net. All the experts agree about this.

“We’ve been doing the right thing, just not enough of it," Edelman explains.

So how do we do more? People have to believe it's necessary and deserved. The conversation has to truly begin. It has to be made honest. Citizens have to talk about how many people need help, why they need help, and what kind of help could actually work. When the false labels are stripped away and that dialogue begins, that's where the solutions will lie.

* * *

Johnny Cash never performed Welfare Cadillac for President Nixon. Deep in a personal battle of conscience about the Vietnam War, Cash chose instead to debut a new song, a slow, melodic poem entitled What is truth? The lyrics speak to a country deeply divided by a perhaps false perception of one another, and they call out to a generation in search of a more honest national dialogue.

What is the truth? The truth of this moment is that the debate over welfare in the US will be largely unchanged by the coronavirus pandemic. The stigma this country has permanently bound to its social safety net is a global case study in the ugliness of a public discourse rooted in racism. Truth, however, is subject to change, and in this case, that change has to be man-made. The very idea of welfare deserves to be re-framed in our national consciousness, and while it may start with the vocabulary, it shouldn't end until our systems and our minds follow.