What our throw-away society can learn from the art of Kintsugi

Humans have always felt compelled to fix things. We are constantly striving to improve our situation, or make our lives better in some way. So when something is broken, it feels natural to go out of our way to put the pieces back together.

But society is changing. In today’s throwaway culture, when something is broken we don’t need to fix it—almost anything can be replaced with something newer, or supposedly better. Many of the things we own are no longer precious, they are disposable.

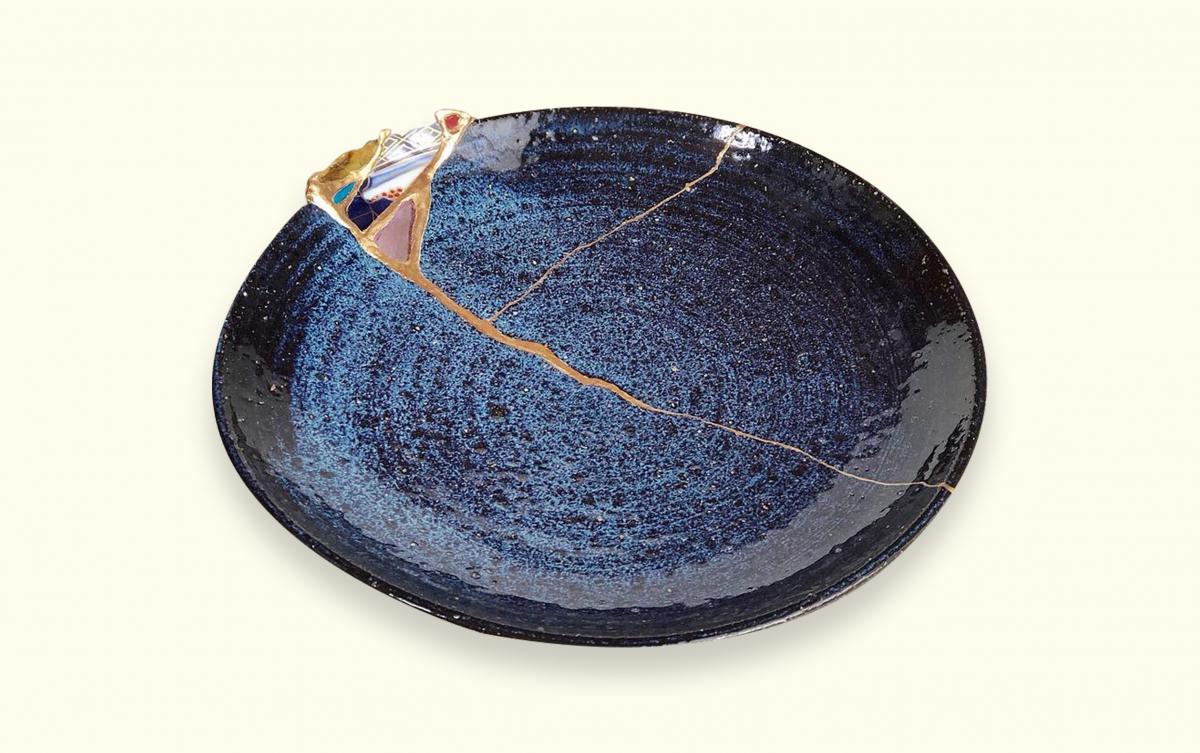

However, one art form challenges us to think about the lives of the things we own. Kintsugi, the Japanese art of golden joinery, takes broken ceramics and puts them back together with their scars on show. By mixing gold, silver, or platinum dust with resin to fill in the cracks, Kintsugi artists are showing the world that just because something was once broken, it does not mean that it doesn’t have a future.

A centuries old practice

Kintsugi is by no means a new practice. The story goes that the art form first began in the 15th Century after a Japanese Shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimasa, broke a Chinese tea set. The set had a lot of sentimental value to the Shogun, and not wanting to throw it away, he sent the pieces back to China where they could be repaired. Although the tea set was returned with all the pieces back together, Yoshimasa was unhappy with the result. The ugly metal staples used to repair the ceramics were cumbersome and unappealing, hardly reflecting the care and love that the Shogun felt for the tea set. As a result, craftspeople in Japan worked to find a more aesthetically pleasing way to repair such items of value. Over time the Kintsugi method was developed and made its way into Japanese culture.

Since then, Japanese craftspeople and artists have developed three different ways to repair an object using Kintsugi. The first is called crack Kintsugi, which is where the repairer puts the pieces from the object back together, leaving spidery veins visible and glowing all over the piece. The second is called the piece method, or makiennaoshi. When a larger fragment of the item is missing, it can be replaced using the gold lacquer, resulting in a glistening chunk of gold in the repaired ceramic. Finally, there is the joint method, called yobitsugi, where the repairer uses a piece from another broken item to make the repair. This results in a patchwork effect, and can bring new life to broken pieces from multiple pieces of pottery.

A philosophy to live by

In Japan, Kintsugi is not just a way of repairing ceramics—it ties in closely with two key schools of philosophical thought: wabi-sabi, and mushin. Wabi-sabi focuses on accepting flaws and imperfections. The idea is that as nothing lasts, nothing is perfect, and nothing is finished, we need to embrace the aesthetic reminders of these facts as part of what makes art and objects unique. And mushin, sometimes translated as “no mind”, is usually associated with the idea of fully existing within the moment, and avoiding being attached to the present—as things change, we must change with them. Kintsugi is an elegant representation of these two ideas, embracing change, and rejecting perfection through the accentuation of flaws in each repair.

Still big in Japan

Although the ideas and practices associated with Kintsugi are centuries old, the art form has an enduring popularity in Japan. When the practice was first popularised, the gold veins were so admired by some that people would deliberately smash priceless artefacts just so they could repair them using the method. Kintsugi and wabi-sabi are also often seen in ceramics used for Chanoyu (tea ceremonies) where repaired or imperfect cups and plates are used to serve drinks.

The younger generation of Japanese artists are also embracing Kintsugi as an art form. Artist, Tomomi Kamoshita, works with pottery and ceramics, but also makes beautiful Kintsugi pieces using the makienaoshi and yobitsugi methods. The repaired areas are often the focal point of her work, and some items, such as the rests for chopsticks, are made entirely of disparate pieces of pottery and broken sea glass found on the shores.

Tomomi Kamoshita.jpg

A piece by artist Tomomi Kamoshita

Kintsugi around the world

While the tradition is still alive and well in Japan, it is also gaining traction worldwide. Kamoshita has been running workshops in New York over the past year, teaching people how to repair or make something new from their broken pottery. Kintsugi is also getting lots of attention in crafting circles, where it combines techniques from popular crafts like mosaics and collages, with the idea of bringing a loved object back to life.

The wider art world is embracing Kintsugi too. For example, artist, Rachel Sussman, has taken Kintsugi to the streets, repairing the cracks in the pavement with gold paint. Sussman highlights the wear and tear of the pavement temporarily, before everyday use makes the gold paint disappear too. Another artist, Charlotte Bailey, has adapted the traditional Kintsugi techniques to incorporate embroidery into the repair of pottery. By covering the broken pieces in fabric, and using golden beading and stitching to put the item back together, she creates beautiful pieces that contrast the softness of fabric with the hard edges of ceramics.

Healing and growing through Kintsugi

The philosophies behind Kintsugi have also started to show up through art forms that explore the healing process. Paris-based artist, Hélène Gugenheim, has used Kintsugi on people with surgical scars. By covering the scars of breast cancer survivors with gold leaf, Gugenheim showed that these marks which usually conjure feelings of pain and suffering, can be celebrated for the fact that they have healed. As word of her work spread, more people began coming to her, asking for their scars to be covered in gold leaf too. The delicate gold leaf makes the scars look precious, and shows that the person is moving forward, embracing the physical changes to their body, and actively choosing to take the next step in their journey.

Another group is also using Kintsugi to help change the perception of the way people heal after surgery. Second Life Toys in Japan takes toys that have seen better days, and takes parts from donor toys to help give them a second lease on life. An elephant may end up with a new trunk from a squirrel tail, or a teddy bear will get two new arms from an old monkey toy. The parts they patch on are never an exact match, but that doesn’t matter—it’s just a new chapter in their journey, and lets them move on to being another kid’s favourite toy. The initiative aims to raise awareness about organ donation, particularly for children. The toys, with their new lease on life, show us how both objects and people change, adapt and grow through the challenges that life throws at us.

In a culture where so much of what we consume is disposable, Kintsugi gives us a framework for thinking about how we could value objects differently. Wabi-sabi and mushin are particularly pertinent in our throwaway culture—they show us how we could treat the life-cycles of objects as a journey, rather than just something there to fulfil a temporary, single use. With the imminent changes that global warming brings, finding beautiful ways to make things last longer and give them meaning could be life changing for us, and for the planet too. Here’s hoping that the future of Kintsugi and the philosophies it teaches stretch across the globe, encouraging us to value what we have, and what we can do to make it last.