The Lovepost sits down with Rushan Abbas, a Uyghur-American activist and co-founder of Campaign for Uyghurs, to discuss her long-standing fight against the Chinese government's persecution of the Uyghur people.

From advocating for democracy as a student in East Turkestan to testifying before the United States Congress, Abbas has dedicated her life to exposing the atrocities faced by her people. In this conversation, she reflects on her journey, the cost of speaking out and what must be done to end the Uyghur genocide.

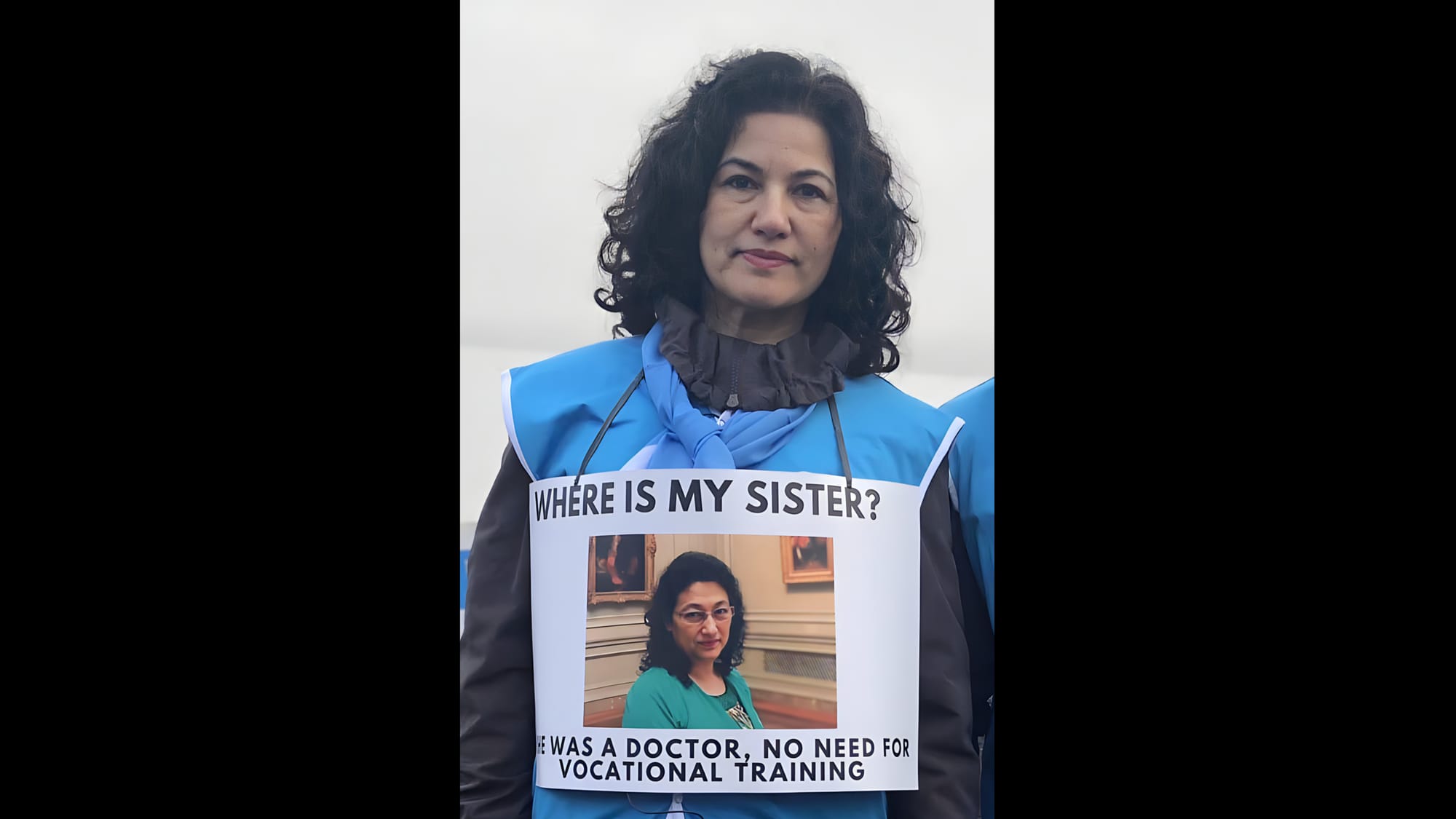

On September 12, 2020, as the world was paralysed by a global pandemic, Rushan Abbas stood outside the Chinese Embassy in Washington, DC, holding a photograph of her sister. The streets were stripped of their usual rhythm, slowed by the uncertainties of COVID-19. Wildfires were scorching the American West, blanketing cities in smoke and forcing thousands to flee. Political tensions were escalating nationwide amid a contentious election season, with debates over pandemic responses and social justice issues at the forefront.

But as the world wrestled with chaos, Abbas brought her own reckoning to the gates of power: a voice for her sister—and for the Uyghur people, whose suffering had been buried under silence and denial.

The day marked two years since her sister, Dr Gulshan Abbas, a retired physician, was disappeared by the Chinese state. Abbas had been protesting across cities and platforms since September 2018, after her family lost contact with her sister and confirmed she had been detained. There were no charges, no trial and no explanation.

"The Chinese official media, [the] . . . Global Times . . . [spread] disinformation, and they spread false narratives about me, and they did an article saying that [I] was stealing other people's [photos], claiming [they were] my missing relatives, and spreading lies about China,” Abbas recalls.

It wasn’t the first time Abbas had stood against the Chinese government, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Abbas’ earliest memories are shadowed by the persecution faced by the Uyghur people. Born in 1967, during China’s Cultural Revolution, she spent her early childhood surrounded by fear and repression. She remembers her mother and father repeatedly being taken away by the Chinese government under different pretences—the government constantly finding new justifications to oppress Uyghurs, shifting their accusations to fit the political climate.

“During the 1950s, Uyghurs were targeted in the name of nationalists," Abbas says. “During the 60s, [during] the Cultural Revolution, [they were labelled] counter revolutionaries. My grandpa was [jailed] for three years. [I have memories of] him talking about the torture he faced in jail and how badly he was treated. His only crime was being an Uyghur.

"Growing up, I used to hear that the Uyghur people have been treated differently. The people disappeared to the prisons, and the Uyghurs [were subjected to] oppression and treated as second class citizens.”

Many Uyghurs were arbitrarily arrested, taken without explanation and often never seen again.

The Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group indigenous to East Turkestan (now officially known by the Chinese government as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region) have long faced marginalisation under successive Chinese regimes. During the Qing dynasty and the Republican era, they were often treated as outsiders in their own land—subject to discrimination and military control. After the Communist Party took power in 1949, repression became systematic: the Chinese state began cracking down on Uyghur identity, imposing sweeping controls on religion, language and political expression in a campaign of forced assimilation.

The state’s grip did not end with Abbas' grandfather. Her father, a respected academic and department chair of biology at Xinjiang University, was “taken away all the time for ‘re-education’,” while her mother was also repeatedly detained.

These were not isolated events—they reflected a larger pattern of targeting Uyghur professionals, thinkers and families. “The people just disappear to the prisons,” Abbas says, and Uyghurs were “always being subject [to] oppression and being treated as second class citizens.” Entire communities were affected. She describes a time when Uyghurs were subjected to what she calls “adverse control policies,” including the large-scale environmental degradation of their homeland. “There [was] very heavy nuclear testing in our region,” she says. “Our region was also used as a dumping ground, bringing Chinese criminals from China proper.”

The nuclear tests she refers to were conducted at Lop Nur in eastern Xinjiang, not far from Uyghur communities. There, the Chinese government carried out more than 40 nuclear detonations between 1964 and 1996. Unlike other regions, local Uyghur populations were neither evacuated nor informed, and many believe they were deliberately exposed, with long-term health and environmental consequences still felt today. The relocation of Han Chinese prisoners into Xinjiang, meanwhile, fed a sense of demographic and cultural erasure. These transfers were part of state-led efforts to assert control over the region by deliberately altering Xinjiang’s ethnic makeup through Han migration and by establishing a dense network of labour camps, prisons and so-called "re-education" facilities. These institutions served as instruments of ideological transformation, aiming to dismantle Uyghur cultural identity and instill loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party. Over time, this infrastructure became embedded in daily life.

These injustices became the foundation of Abbas' political awakening. “So many different things,” she says, “made me feel that the Uyghurs need to live with dignity, and we need to speak out.” It was this convergence of personal experience and collective trauma that pushed her towards activism.

By the time she began university, she had a firm grasp of the political situation in East Turkestan. As a university student in Ürümqi, Abbas became actively involved in pro-democracy movements and rallies. Surrounded by a generation of Uyghur youth seeking greater freedom, she began speaking out about the discrimination and restrictions her community faced. In 1985 and again in 1988, she helped organise student demonstrations calling for democratic reform and expanded rights for Uyghurs. Her political involvement, however, had consequences.

After graduating in 1988 with the second-highest score in Xinjiang University's biology department, Abbas was unable to secure employment—a result she attributes to government retaliation for her activism. Recognising the risks she faced, her father encouraged her to pursue studies abroad. Leveraging his academic connections, he helped arrange for her to become a visiting scholar at Washington State University.

She arrived in the United States in May 1989, just three weeks before the Tiananmen Square massacre—a moment that reinforced everything she had come to understand about state violence.

In April 1989, following the death of reformist leader Hu Yaobang, thousands of students, intellectuals and workers gathered in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square to demand democratic reforms. Frustrated by widespread corruption within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and inspired by global democratic movements, protesters called for freedom of speech, press and assembly. The demonstrations grew into one of the largest pro-democracy movements in China’s history, with protests spreading across the country.

On the night of June 3rd, after months of peaceful demonstrations, the Chinese government declared martial law and deployed troops to Tiananmen Square.

Reflecting on that day, Abbas says, “Chinese students were protesting in Beijing, Tiananmen Square [for months], demanding respect for human rights. They were demanding freedom and democracy. But the Chinese military marched in in the middle of the night, and massacred the students.” Estimates of the death toll vary, as the Chinese government has suppressed records of the event, but reports suggest that hundreds—possibly thousands—were killed, while many more were arrested or disappeared.

Watching the Chinese government “crush innocent Chinese students—their own children,” made Abbas further understand the pattern of state oppression. It made her realise she shouldn’t be surprised by the way Uyghurs were treated, or by the human rights abuses unfolding in places like Tibet and Southern Mongolia.

The brutal suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests sparked international condemnation, but the backlash was short-lived. The swift return to business as usual revealed a hard truth: for many countries, economic ties mattered more than political concerns—an insight that would shape China’s internal and foreign policy moving forward.

In the years after the massacre, the Chinese government intensified its control over Xinjiang, stating concerns over separatism and religious extremism. In April 1990, the Baren Township conflict erupted when Uyghur militants clashed with Chinese forces, leading to numerous casualties and arrests. Subsequent years saw increased surveillance, restrictions on religious practices, and crackdowns on dissent, exemplified by the 1997 Ghulja incident, where peaceful protests were met with lethal force. These events marked a period of escalating repression that set the stage for the more systematic policies implemented in the following decades.

In 2013, China implemented the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)—a massive global infrastructure project aimed at expanding China’s economic and trade networks. Ironically, the initiative was launched in the very region that had long served as China’s dumping ground—a remote frontier where Uyghurs were repressed, and prisoners were exiled. East Turkestan had long been a key trade hub, given its strategic location along routes connecting China to Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe. With the launch of the BRI, its importance grew even more, and Beijing intensified efforts to secure full control over the region. Major trade routes, pipelines and railway networks were expanded, reinforcing its role as a gateway. To ensure stability for its economic ambitions, the CCP escalated its long-standing repression of the Uyghurs, tightening surveillance and policing under the guise of national security.

This growing crackdown led to one of the most devastating human rights violations in modern history. Abbas explains: “The Chinese government had immediately started an order to build concentration camps in the north.” The first of these facilities was built in 2014, but by April 2017, reports surfaced of mass internment and the forced disappearance of Uyghur people. By the summer of 2017, an estimated three million people had gone missing—swept into a vast network of internment camps and forced labour facilities. While the Chinese government has denied wrongdoing, survivors and investigators say many detainees were never heard from again, and the full extent of the disappearances remains unknown to this day.

"Almost everybody was targeted: the thought leaders, intellectuals, famous writers, educators and university presidents and professors, pop stars. Anybody who has a name that is influential in society [was] targeted,” Abbas says.

Abbas provides insight into what was transpiring in the camps, drawing on a series of leaked Chinese government documents and investigative reports that exposed the scope of the repression. The China Cables revealed official guidelines for managing the internment camps, including surveillance protocols and ideological indoctrination. The Xinjiang Police Files, leaked in 2022, provided internal police documents and photographs that documented arbitrary detentions and the brutal conditions inside the facilities. Other reports, including those from the United Nations and human rights groups, detailed the use of forced sterilisation, abortions and sexual abuse—often carried out in detainees’ homes during so-called “home stays.” Uyghur children were also forcibly separated from their families and placed in state-run orphanages, while men were sent to concentration camps, forced labour programs or high-security prisons.

These abuses persist to this day. Mass internment has evolved into a system where Uyghur men and women are compelled to work in factories feeding global supply chains—producing goods such as cotton, electronics and textiles. Despite mounting international scrutiny, products linked to forced Uyghur labour continue to reach global markets.

“While the Chinese government is making Uyghur women's bodies the battleground of this genocide, they are making profit off this genocide by using Uyghur slaves in the supply chains for so many companies around the world,” Abbas says.

Abbas also speaks about how the crackdown shook her own family. “My husband lost contact with his entire family: my parents in-law, three of my sisters in-law, their husbands, brother in-law and his wife, and 14 of my husband's nieces and nephews went missing.”

Devastated by these blatant violations of human rights, and enraged at the thought of the government being unhindered in its mission to eradicate the Uyghur people, Abbas began to think of a way to combat these issues. In September 2017, she co-founded Campaign for Uyghurs, a non-profit organisation dedicated to promoting and advocating for the human rights and democratic freedoms of Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in East Turkistan. The organisation places a strong emphasis on empowering Uyghur women and youth, building solidarity with other persecuted communities, and supporting wellbeing through initiatives such as the Uyghur Wellness Initiative. Its efforts have earned international recognition, including Nobel Peace Prize nominations in 2022 and 2025 for advancing human rights and promoting justice in the face of repression.

Abbas explains that the mission of Campaign for Uyghurs is to combat the ongoing Uyghur genocide and to counter China’s false narratives, which are laden with disinformation, misinformation and false narratives. “We are trying to mobilise global grassroots organisations and civil societies, and we place a strong emphasis on empowering the Uyghur diaspora,” Abbas says.

For Abbas, it is just as important to celebrate and preserve the beauty of Uyghur culture as it is to advocate against its erasure. Her mission goes beyond raising awareness—she aims to equip Uyghurs with the tools to advocate for themselves. Whether through training programs, legal education or creating a sense of community, she seeks to create spaces where Uyghurs can connect, support one another and reclaim their identity through shared experience.

At the heart of the organisation’s work are workshops designed to empower participants with practical advocacy skills. Abbas explains that these programs are meant to “equip them with essential skills [such as] organising, advocacy, media engagement and navigating democratic systems.”

Education and awareness are key, especially when it comes to understanding the complexities of legislative systems—systems that so often impact society’s most vulnerable, including women, the elderly and children. Abbas emphasises that their work extends beyond training: “We also engage directors, policymakers, international stakeholders and the public, providing them with the evidence and reality of what's happening to Uyghur people today, [to] ensure that the voices of those suffering are heard and acted upon.”

Within just a year after launching, Abbas and her team began reshaping public understanding of the Uyghur crisis. Their advocacy helped build global awareness of the reasons behind the persecution, connecting it to broader human rights concerns and geopolitical dynamics. In September 2018, Abbas spoke at a Hudson Institute panel titled “China’s ‘War on Terrorism’ and the Xinjiang Emergency,” where she delivered harrowing testimonies from victims who had been threatened, detained or disappeared. She described in detail the inhumane conditions inside the so-called “re-education camps,” offering firsthand evidence of the psychological torture, overcrowding and ideological indoctrination faced by Uyghur detainees.

This advocacy came at a personal cost: mere days after the panel was published, her sister was arrested. Abbas thinks back to this painful time: “The Chinese government arrested my sister as [an act of] transnational repression, as retaliation for my activism. My freedom of speech in the United States as an American citizen cost my own sister’s freedom.”

What began as advocacy evolved into a mission. With her sister taken, Abbas’ fight for justice became all-consuming.

“I quit my full-time job and became a full time activist. I was writing articles, giving interviews and going around the world protesting and holding her picture. [I was] protesting in front of the UN, the European Parliament and the Chinese Embassy in Washington, DC,” she says.

During this time, the Chinese government tried on many occasions to discredit her work, completely denying the allegations and claiming she was displaying a photo of a stranger with no relation to her. She reflects on this with satisfaction: “I just ignored everything, and doubled down my efforts each time the Chinese government [or] Chinese officials attacked me. I take [their reaction] as [an] impact of my work. I take it as the Chinese government [being] scared from the truth that I'm speaking out, and I just continuously fight harder.”

In late 2020, Abbas finally learned what had happened to her sister. “More than two years after her arrest, we heard from a third party that she was arrested [and] sentenced to 20 years on terrorism-related charges,” Abbas shares. “We immediately called a press conference at [Capitol] Hill with several lawmakers, [who] demanded her release, and the next day, it was publicised heavily in mainstream media, including AP, BBC, Al Jazeera and Reuters.”

A day after the press conference, a Reuters reporter raised Gulshan Abbas’ case with Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin. For the first time, a Chinese official publicly acknowledged her detention. “Gulshan Abbas is charged [in] accordance with Chinese law for her crimes,” he said. This contradicted previous state media claims that Abbas had fabricated her sister’s existence.

Abbas remembers what ran through her mind at the time: “You cannot even keep up with your own lies. Didn’t you say a year ago that I was faking and my sister did not exist and I was stealing other people’s photos and spreading lies about China— and today you admit that you have her? So . . . which one? Am I a liar, or is she a criminal?”

Abbas’ determination has only grown stronger in the years since her sister’s disappearance. More than six years on, she says not a day passes without thinking of her—and that longing, she explains, is what fuels her fight. Her love for her sister, her people and for democratic values continues to drive her activism forward.

Abbas’ fight is part of a collective struggle, one where women’s voices must be heard. Advocacy through women has been one of the underlying themes in Abbas’ organisation, and she highlights the integral role that women play in the discourse surrounding social and political change.

“The bodies of the Uyghur women are the true, true battleground of this genocide,” she says. “Who speaks the most effectively for Uyghur women who are suffering so much? The women. They need to be the voice for those millions of suffering, the Uyghur women.”

The bodies of Uyghur women have been so deeply politicised that they are denied the autonomy to bear and raise children according to their own beliefs, enabling the government to not only control the population, but also impose its narratives upon the next generation.

“Every Uyghur woman living outside of East Turkestan, [knows] the deep wounds of their mothers, sisters, daughters, friends and neighbours, [and] what they are enduring in East Turkestan. They carry the lived experiences and the profound emotional connections to the injustice faced by their families. Their voices are powerful . . . and listening to their stories has driven meaningful change that has resonated with women all around the world.”

Yet while Uyghur women continue to speak out and mobilise, it is also important to critique what other countries have done—or failed to do—to stop this genocide, and analyse the role we as a society have played in the debate over civil rights legislation.

Abbas expresses disappointment in the international community's response, particularly that of the United Nations. “To be honest with you, I am disappointed in the UN, " Abbas says. The UN was established . . . to avoid such atrocities after World War II, and there is a vow: Never again. But when it comes down to the Uyghur genocide, [the] UN has been awfully silent.”

She explains that despite being presented with reports explicitly detailing the oppression of Uyghurs, the UN has failed to fully address these issues or implement viable solutions. “There is no neutrality when it comes down to genocide. We are fighting between right and wrong; good and evil.”

Reflecting on how far her journey has taken her, Abbas speaks about the progress she has seen in her advocacy since the 1980s. She recalls, “When I started my advocacy, the word ‘Uyghur’ was not known. We had to explain who the Uyghurs are. We had to explain what's happening to them, and now . . . we have bipartisan support at the US Congress, we have really strong support in the EU and we are trying to educate the general public. We are actually making some pretty positive progress.”

One way this information is being made more accessible is through the documentary In Search of My Sister, a 2022 film by Jawad Mir that explores Abbas’ advocacy, the persecution of Uyghurs in China and her sister’s detention. The film has been screened in 38 countries and is offered alongside advocacy workshops.

But the impact hasn’t stopped at awareness. Years of persistent advocacy—from Abbas and a growing global movement—have begun to shape policy. Two landmark US laws—the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act (2020) and the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (2021)—represent concrete steps in the global response to the crisis.

The first mandates that federal agencies investigate and publicly report on abuses by the Chinese government, including mass internment, surveillance and forced disappearances. It also authorises sanctions against individuals responsible for these violations. The second, even more sweeping in its impact, bars imports from Xinjiang unless companies can prove their goods are not tied to forced labour— shifting the burden of proof onto corporations.

Abbas believes these laws signal something that once felt impossible: institutional acknowledgment of a cause she has spent decades trying to get the world to see.

When asked how society and advocates can better support and inform the public about the mass genocide of Uyghurs and other oppressed groups, Abbas emphasises: “It is extremely important to amplify the Uyghur activists and the Uyghur victims’ and former camp victims’ voices. We need to address [these issues] in our own society with our lawmakers [and] politicians—[to] not be complicit in this genocide by buying the goods manufactured by Uyghur slaves’ blood, sweat and tears.”

Building communities that support and advocate for these populations is at the heart of liberation and equal human rights. It is not enough to simply be aware—action and education are essential. Abbas urges people to continue fighting for marginalised communities, drawing inspiration from Dr Martin Luther King Jr: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” she quotes, adding, “and I believe that justice will prevail.”

The fight for justice needs you. Stay informed. Get involved.

Follow @campaignforuyghurs on all social media platforms.

Take action at Campaign for Uyghurs.

Further reading:

No Escape: The True Story of China’s Genocide of the Uyghurs by Nury Turkel

Turkel was born in a re-education camp in China and tells both his story and the broader Uyghur struggle from an insider’s perspective.

This is probably the most authentic and authoritative English-language book by a Uyghur voice on this issue.

The War on the Uyghurs: China’s Campaign Against Xinjiang’s Muslims by Sean R. Roberts

A scholar of Central Asian politics, Roberts draws on years of research to explain how China framed Uyghur identity and Islamic practice as threats to justify mass repression.

A comprehensive and accessible English-language accounts of how the so-called “War on Terror” was used to enable a modern-day system of internment and control.

Other important Uyghur Voices (in essays and reports):

Rushan Abbas: Speeches and op-eds (e.g. Washington Post, Foreign Policy)

Jewher Ilham: Daughter of jailed Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti, she has spoken and written extensively.

Zumret Dawut: Former detainee, speaks about her forced sterilisation and life in the camps.

Gulchehra Hoja: Former Chinese state TV journalist, now Radio Free Asia reporter, with powerful personal writing and testimony.