Trigger warning: This story discusses themes related to medically assisted dying and suicide. It may contain descriptions of difficult emotional experiences and discussions about end-of-life choices that some readers may find distressing.

The issue of medically assisted dying arouses strong feelings in all directions.

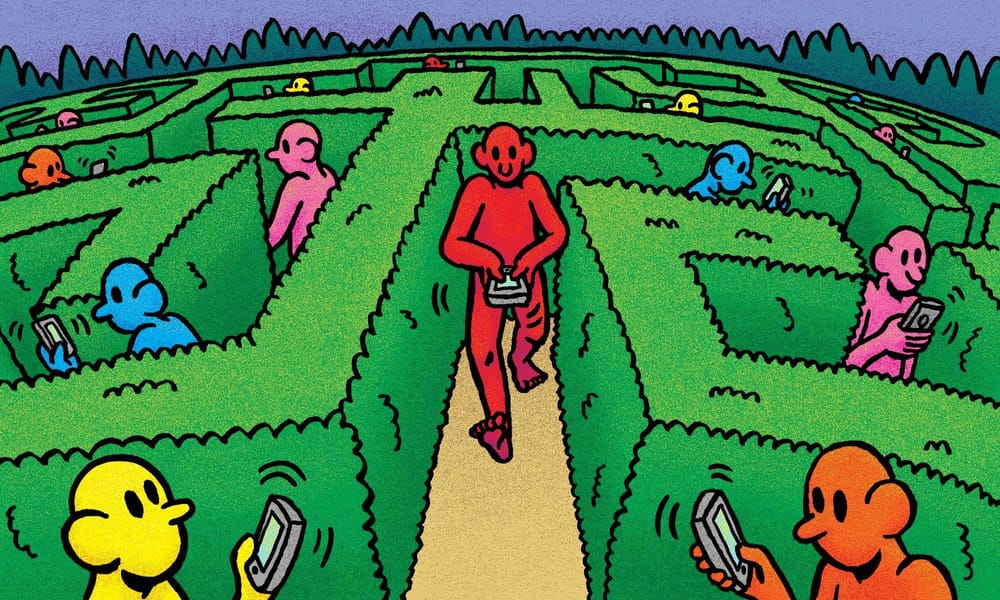

In the view of some critics, medically assisted dying is a slippery slope to a dystopian nightmare in which health practitioners simply "give up" their efforts to relieve distress and patients come to see death as an easy solution to their problems. Proponents, on the other hand, often argue that no one should be forced to endure unbearable suffering against their will and that medical assistance in dying (MAiD) can be consistent with, rather than a violation of, the medical principle to "do no harm".

One physician-pioneer in the field of MAiD is Dr Stefanie Green. Dr Green grew up in Nova Scotia, Canada, and studied medicine at McGill University. She had spent more than 20 years as a family doctor specialising in maternity and newborn care when a landmark ruling by the Canadian Supreme Court captured her attention. This was Carter vs Canada (Attorney General) 2015, which saw judges unanimously strike down the prohibition of physician-assisted dying as a violation of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Having always been interested in the intersection between medicine, ethics and law, Dr Green refocused her work on medically assisted dying and co-founded the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers (CAMAP) in 2016. Under her expert guidance and advocacy, CAMAP evolved from a grassroots network of clinicians into a national professional organisation that today offers – among many other things – the Canadian MAiD Curriculum, a nationally accredited educational program for licensed nurse practitioners and physicians to support the practice of MAiD.

Dr Green published her bestselling memoir This is Assisted Dying: A Doctor's Story of Empowering Patients at the End of Life in 2022 and has received international acclaim for her advocacy work.

The Lovepost sat down with Dr Green to discuss the legality and ethics of MAiD as it is currently practised in Canada.

You began your career in obstetrics before shifting to focus on medically assisted dying in 2016 when it was legalised in Canada. Looking back, what prompted that shift? Is there a relationship between those specialities?

Yeah. I actually come from a background in family medicine, where I chose to specialise in maternity and newborn care. I'm not an obstetrician-gynaecologist; I am trained as a family doctor. I did that for over 22 years, and I loved it. It was a real passion of mine. I adored my career, I was one of those few happy doctors that you come across [laughs].

In 2016 . . . a number of things came together at the same time. One of them is that after so long in the field—doing calls at the hospital, taking care of women—it was becoming physically hard to spend 24 hours in the hospital, see emergencies and then recover the next day, and still balance the other responsibilities of my life. I was getting some pressure from home to maybe cut back a bit or look for other options. At the same time, my children were growing up and about to leave, and I wanted to be a little bit more present in their lives.

At the same time, this interesting court case was happening in Canada. I'd always followed this journey of end-of-life options—the argument and the debate about assisted dying, since my early days in medical school . . . and I thought, “Who's going to do this work? It's so important. Who's going to step forward and do that?” I've always been interested in that intersection between medicine, ethics, and law, and have always found that outlet in other ways in my career. But this [challenging Canada’s restrictions on the right to assisted dying] really kind of called to me and my interest. The opportunity came along, and I was really interested in it. The more I learned about it, the more I felt it was important. It drew me to the idea of patient-centred care, which is something that's always been incredibly important to me in my work, and I thought this was the ultimate fulfilment of that. So, I made this switch in 2016.

I love the question about the similarities between the two because people often seem shocked that I've gone from the beginning of life to the end of life. But the truth is, there are a lot of parallels, a tremendous amount. It occurred to me fairly early on that I was extremely grateful to have this background in maternity care because my skill set was completely transferable. When you work in maternity and newborn care, the role is to be a knowledgeable guide to your patients, to help them prepare for this tumultuous transition from person to parent, from couple to family. There's a big transition that's going to happen and whether it's physical preparation or knowledge preparation, getting them ready for that change and then being present with them for labour and delivery is this incredibly intense and emotional day, and there's family dynamics at play. It's one of the most important days of their life. There is this natural event unfolding with unclear consequences that could happen at any time. It's really a very dynamic interaction. And yet, I am clearly not the most important person in the room. The mother and baby, this dyad is the most important, and hopefully, all goes well and you place this baby onto mom's chest, and there's this magical moment happening. It's not for me to stay and celebrate, it's for me to gracefully withdraw and leave this, for lack of a better word, sacred moment with this family.

Everything I just said about maternity and newborn care and my role in it, could be said for assisted dying at the end of life. It's all those things as well: most important day, very emotional, very intense, I'm not the most important person there, there’s family dynamics, and it’s time for me to withdraw. All of this stuff is true. So, this skill set was much more easily transferred to end-of-life than I expected. And I'm constantly being shown these parallels between beginning and end of life which I find academically really fascinating.

That’s such a fascinating comparison. From your description, there seems to be an intuitive resonance between those fields. When you were moving into medically assisted dying, did you support the right to die? Or were you on the fence until you came to an educated decision?

It's an interesting question. I began thinking about assisted dying in medical school when the Sue Rodriguez case was blasted across the newspaper. I was taking the bioethics course and trying to understand terminology for the first time. I'd never really considered assisted dying when I was in my 20s. I became aware of it and watched this story [unfold], where just from a certain personal perspective, you read this woman's story and feel pulled towards her. There's a lot of empathy for her situation. There's no doubt that my view of assisted dying was shaped by that experience.

One of the central themes of my practice in maternity care, one of the things that I loved about it [through] the way that I saw labour and delivery consistently, is that the birth of a child can be an incredibly empowering moment for a woman. I think it can heal trauma, I think that it can bring joy, and I think that it can be an incredibly empowering thing to help a woman realise that she can do this, even though she's doubtful that she can. And then at the end, if you can do this—if you can grow a baby inside you, and you can birth it and feed it, which your body does naturally if you just let it—it's amazing. You can frame it in that context, and women feel incredibly—as they should—proud of themselves and empowered by that. So that empowerment has been a central, core feature of my practice.

I was drawn to assisted dying because I saw that. Even before I did more research, I could see how people who had been suffering for weeks, months, or years with an illness, had . . . any sort of sense of control of their life [taken] away from them, because they were so beholden to the illness itself. As it progressed, [I saw it] even more so; that giving them this sense of control at the end might be the first time they'd had that sense of control for a very long time. I could see how it could be empowering to them, and I was drawn to that notion right away. And yes, the more I learned, the more I understood that role and the ethics around it. I felt comfortable with it. I think I was prone to being supportive of it because of my background.

Before I go further, our readers are international so can you please take us through the mechanics of assisted dying in Canada?

There is a very rigorous model of eligibility that has to be followed in order to be eligible for an assisted death in Canada. It's not as simple as some people think. There are some things that just need to be true, and they need to be verified by more than one clinician. So if a person in Canada wants to access assisted dying they have to be the ones to ask for it. Assisted dying has to be triggered by the patient themselves, always.

Can the medical practitioner suggest Medical Assistance In Dying [MAID] as an option? Can they make a patient aware of it?

The federal law states clearly that to counsel someone to suicide remains . . . a criminal offence in Canada. I think what was misunderstood in the early days was exactly what that meant. The word ‘counsel’ in legal terms means to promote something: to counsel someone to commit suicide, for lack of a better way of saying that, means, “Here's a gun, I think you should use it,” right? To encourage someone. Counselling in medical terms is not used that way. To counsel someone in medicine is to inform them. We counsel people to quit smoking, we counsel people to change their lifestyles. That's a common use of the wording in health circles. And so to promote suicide to someone, to encourage someone, it remains a criminal offence.

But imagine I have . . . a conversation with a patient who is already discussing their end-of-life options, or their goals of care at end of life, and you're discussing palliative care, and you're discussing supportive care and discussing active treatment. In such a situation, it would be very appropriate and some might say professionally an obligation to not say, “Hey, have you thought of…” but to say, “In Canada, we now have the legal ability to consider other alternatives of [the] end of life. It's called assisted dying. Is that something you're aware of? Would you like more information on that?” To ask permission to talk about this topic. People will quickly tell you, “I don't want to hear about that,” or “Hey, I have heard about that. Can you tell me more?” So I think when discussing end-of-life options, this is one of them that is legal, is medically covered, and is medical care in Canada. To not offer that in a specific situation, to be extreme, it is malpractice. That doesn't mean that someone on a telephone call with a caseworker at Veterans Affairs should be discussing MAID with someone who's asking for a [way out of their lives]. That is completely inappropriate and out of their lane; a horrible misstep. But yes, there are times when I think a clinician should be able to bring it up appropriately.

So, when critics worry that offering MAID as an option will be received as an advocacy of MAID, that’s scare-mongering. You’re saying that’s not how it happens in practice.

Exactly. The patient has to ask for it . . . in a written form, and there's formal paperwork that has to be filled out. It has to be signed, it has to be dated, [and] there have to be witnesses. [There are] a number of procedural safeguards around that process on its own. Once it's requested, the process says that the patient needs to be seen by two different independent clinicians, either a medical doctor or a nurse practitioner (Canada allows for both) to see and assess the patient for eligibility. Do they meet the medical criteria for assisted dying? Those people need to be independent from each other—they can't be married, they shouldn't have a hierarchy to each other.

In the simplest of terms, I always say there are essentially five things that need to be true. And they are, very briefly, a person needs to be over 18 years of age. It's an arbitrary line. They need to have Canadian government-funded healthcare. No tourists can come to Canada and receive this. They need to make a voluntary request. No sense of coercion from anywhere else—not an angry spouse, not a greedy child—it has to be a voluntary request. They need to have the capacity to make this request. So part of my job is to ensure that they understand what's wrong with them, that they can appreciate what their treatment options are, the pros and cons of that, to ask questions about that information, to be able to articulate their own request and give informed consent. So, capacity and informed consent must be present.

The last thing is that they have to have what the Canadian law calls a grievous and irremediable condition. A lot of big words, the definition of which is actually in the Criminal Code of Canada. So as far as I'm aware, it's the only medical practice that's in the Criminal Code of Canada. The definition of a grievous and irremediable condition requires three things to be true. [Firstly] that a patient has a serious illness, disease or disability. That they are in what's called an advanced state of declining capability, meaning they're no longer functioning in the way that they were before their serious illness, disease, or disability. And that they are suffering in a way that they believe is intolerable, and that cannot be fixed, or addressed in a way that they deem acceptable. So they have to have an incurable illness, they have to have an irreversible decline in capability and they have to be suffering intolerably. All of those things need to be true.

Once those things are deemed to be true by one of the assessors and then the other assessor, the patient is given the ability to make a decision to go ahead or not go ahead. They can certainly change their mind, but it means all the hoops have been gone through, and they are then empowered to have that choice.

There are two pathways to access assisted dying once all eligibility are met. Track one is for patients whose natural death is reasonably foreseeable. That does not require terminal illness. That means they're on a trajectory towards the end of their life due to their serious illness, disease or disability. The most common example is of someone with stage four pancreatic cancer. No one's going to argue, right? So, their death is reasonably foreseeable. There are a number of safeguards that are pretty straightforward that have to be met. If, on the other hand, their death is not reasonably foreseeable—let’s say they have a chronic pain syndrome or genetic disorder that's left them in a place where they progressed to the point where they're suffering intolerably, but they're not actually dying from it—then they have all the same safeguards from track one plus an additional five. And it's much more cumbersome.

Some critics say that the ability to give meaningful consent is contravened by the very fact that the patient is asking to die.

Well, that comment presumes that no one can ever have a rational choice to want to end their life. I think that's a statement that is controversial, at best, probably paternalistic and certainly not understanding of the patients that I see in the way they express themselves. I mean, just anecdotally, I see hundreds of patients. I see patients who tell me and explain very clearly. I saw a lady . . . two days ago. She's sitting on her couch in the living room—she actually happens to have metastatic pancreatic cancer . . . and she's a 77-year-old woman, a very pragmatic woman who's seen her husband die from lung cancer, who's seen her parents die from other cancers, has seen that decline, that death trajectory. She has done treatment, and she has done all the things that she wanted to do and felt were important to do, and now it’s a stage where she's been overwhelmed by her illness. She is getting weaker and weaker. And she knows exactly what she's facing, she knows what her options are, she knows what palliative care can offer her at home. She knows what she can be offered at hospice and hospital. She has a plethora of options in front of her. And she very clearly, with a very clear mind, says to me, “I understand all of that.” She said—her words—which I disagree with, she says, “I do not have the courage to go through those final weeks and months of decline. That's not what I want. I've seen it, I know what it is. It's not what I want for me, it's not what I want for my family. It's not what I want. And when I hit a certain point, I would prefer to have an assisted death. And these are the reasons why, and this is where I'd like it to be.” She makes a very logical, very rational, fully capable, fully informed decision. To say to someone that that is not a rational decision seems absurd to me. Blatantly untrue. I think there is such a thing as a rational wish to end your life, and I think that this law allows for that.

How do you think we can account for that kind of denialism? Why is there such widespread stigma around medically assisted dying, and even around suicidality or desire to die for whatever reason? How do you account for that stigma?

How do I account for stigma? I account for all stigma by ignorance and fear. Stigma is based on ignorance and fear, and this is really no different. I don't want to discount the importance of suicidality, and its place and its presence in much of our society. I mean, it exists, it is a problem, it is something that deserves attention. Suicide prevention is a very important measure that our communities need to continue to do.

When patients show up in my office and start talking to me about assisted dying, I need to assess whether they are irrationally suicidal. Whether they have a mental health disorder that is affecting their capacity and their mental state. It's important for me to be able to tease that out and to always address what is going on. Why are they seeking this information? What's really happening? So, I think suicide prevention remains an important element in society, and we need to approach patients and anybody who is suicidal . . . to be cared for in the same way. Do they have a plan? Do they have a means? Are they a harm to themselves? There's a whole branch of care that still needs to happen. That is, in my opinion, very different from a lady on her couch in her living room who's talking to me about a rational decision to end her life due to her illness.

I think the distinction can be made. I know that there are psychiatrists who disagree with me and say that you can't distinguish between the two. I would invite them to spend a day with me and see if they feel the same way. I mean that not disrespectfully. I think there are cases where it can be complex, and I don't suggest that I'm an expert in the field of psychiatry, but I can certainly distinguish when someone's making a rational and informed decision to end their life. I think the distinction is clear.

The Canadian government is, after some delay, now expanding the legislation to extend eligibility to those suffering from mental illness. This has caused some controversy, and the Canadian Mental Health Association isn't supportive. What are your thoughts on this change?

I need to correct headlines screaming about the expansion of MAID law. This is not an expansion of our MAID law. The reason this [MAID] law exists in Canada is because of a high court decision. Not because patients demanded it, not because the government thought it was a good idea. There was a Supreme Court decision based on a constitutional argument not to give the right to die to patients.

That's not what happens. In Canada, there used to be a blanket prohibition against assisted dying. That blanket prohibition was deemed to be unconstitutional because, in certain circumstances, with certain people, that would be an infringement on their rights. That's what the court said. So there's no [longer a] blanket prohibition [against MAID].

[Then] the government decided [MAID] may need some regulation. [In 2021] the government, for the very first time, excluded patients with mental health disorders as their sole underlying condition from accessing MAID, specifically and explicitly. What's happening in March of 2024 is not an expansion of our MAID law. It is a restoration of the rights of those with mental health disorders to access legally covered medical care, one aspect of it in this country.

Thank you, that’s clearer. How do you feel about people with mental health disorders having their right to access MAID restored?

This is a complex issue, but I don't believe that mental health disorders, or patients with those, should be particularly stigmatised or singled out as the most complex patients. First of all, I've been dealing with patients with mental health disorders who have a comorbid physical illness for seven years. It's not as if people who do this work have not considered how to assess capacity and people or whether their mental health disorder is interfering with that capacity. We've been doing this. It's not as if we have never dealt with this patient population. We have. In fact, there are situations [with] people who do not have mental health disorders but only physical illnesses, who have extraordinarily complex cases that I need to tease through, and that I can't sort out. It's not because they have a mental health disorder that they're complex. It's because complex situations are complex.

Some of them, yes, have mental health disorders. I think to stigmatise this patient population only, is a disservice to them. It's something we've been trying to work against for decades, so this isn't helping. That said, I am not a specialist in psychiatry. I will seek out the expertise of my colleagues in that field to help me sort out how I can or cannot say if someone's illness is irremediable. To be irremediable, it's not because you've . . . broken up with your boyfriend at age 26. It's not because you've had your first episode of psychosis at 24. It's not because you've had one or two episodes of depression and the first time it went away with medication, but the second time you didn't want to take it, and now you're fed up. That's not irremediable.

Irremediable means long years of documented illness that has been treated, and treatment has failed repeatedly over time, despite a multitude of treatment trials, with a number of professionals, that's lasted a long time, and that you are at a place now where you believe it's unendurable. You need to make a lot of things be true before I can have a medical opinion that it's irremediable. So for the 100 people that apply for this, maybe one will qualify under our current law and regulations because of what's required. I say that based on data in other countries where they do allow patients with mental health disorders to access MAID, and we see it's a very small number of patients. I don't expect that will be different in Canada—why would it be? I think that the requirements are robust. To suggest that it's a simple matter . . . is not recognising the rigorousness of what's required.

You’re saying it's a straw man to say that someone who's just been broken up with at 26 is going to suddenly seek out MAID?

Well, I think that as the headlines continue to be perpetrated, like, “Man facing eviction, going to choose MAID instead,” I will say, anyone who's broken up with their girlfriend or has been threatened with eviction, anyone in Canada can ask for an assessment for an assisted death—that doesn't mean they will be found eligible. We have to have a little bit of confidence and trust in the people who do this work. Nobody does this lightly. Nobody does it carefree or flippantly. There is a rigorous system in place with robust safeguards. These cases need to be assessed carefully and cautiously, and they are. We have no reason or evidence to think anything other than that careful, cautious approach has been taken for seven years. I don't see why that would change going forward.

I want to push this just a little further because it’s an important intersection. If suicide prevention efforts have failed for a person, does MAID become a possibility of last resort?

MAID is only a possibility if people meet all the eligibility requirements. People often think of suicide as [concerning] someone with a mental health disorder. If someone has something that's interfering with their mental state and it's causing them to be acutely suicidal, they're not going to qualify for MAID. Some people will successfully suicide. As terrible as it sounds, that is something that does happen. If someone comes to me and says, “If you don't offer me an assisted death, I'm going to kill myself,” that doesn't make them eligible for MAID.

That would actually make them completely ineligible, from what you’ve described.

In my mind, that would put up a really big red flag. First of all . . . you can't threaten me into offering you MAID. That's not going to work. And then, I would work very deeply at looking into what makes them want to end their life. I'd have to tease out whether they're capable or not.

People stop and ask the question, [but] they stop taking it forward. Just because you ask for MAID or threatened for this doesn't mean you're going to get it, that's the message. It's difficult to qualify. It's not so difficult if you have a terminal illness and are clearly dying in the next three months—to be honest, those cases are not so complex to assess. If you look at the statistics, you know, track one, track two natural deaths, reasonably foreseeable, or not. [They constitute] 97.8 percent of all MAID deaths in Canada. We're talking about [almost] 98 percent of all MAID deaths in Canada [being] track one patients. There [is] two percent that are track two.

Thank you for that context. Within this robust assessment, you must still be called upon to make very difficult judgements. Can I ask about the assessments that you found to be more ethically complex?

One of the earliest track two patients I took when it first became legal in 2021, when patients whose death was not reasonably foreseeable had access to MAID. [It] was a case which I never thought that I would accept or look into or assist for. I say that with permission of the family and the patient themselves. This was a youngish man, somewhere in his 40s, who had a wife and children; a man who worked in the healthcare field in some way—I'm not going to go into a lot of personal detail. A robust, fit, active guy. He had been diagnosed with and suffering from something that when I went to medical school, in the dinosaur age, in the 90s, was considered not even a real diagnosis. He had what he called Chronic Fatigue Syndrome—very misunderstood. People will still to this day wonder if that's just all in their head.

This application comes through, and I'm looking at it, thinking, “What?” This work has taught me that you need to get rid of your preconceived notions, you need to go with an open mind—not so open that your brain falls out, but open enough to really understand what people are going through. Because until you're in someone's shoes you don't understand, and people's experiences are different [from] what I think.

I took the case and I thought, this is the only way I'm going to learn about this—I'm going to go in as open-minded as I can. But clearly, I’ve got to say, I was sceptical. I'd seen a couple of other people with that diagnosis, some questionably so, and others who were really very disabled by their disease. Anyway . . . I saw this guy. I understood what was going on. I saw how long it had lasted, I saw the depth of his disability, I saw the work that his wife had done to research options. I'd seen all the reports. He was very well-connected, he saw a lot of people. He saw specialists and he had phenomenal care. Most people would be grateful to have this level of attention and care for such an obscure, or no longer obscure, illness. And he had tried many things and I was able to [document] it. [It] took me 10 months to work through all his records, to be able to document everything, and speak to him several times.

At some point, I stood back and looked at the eligibility criteria and I talked them through, and I thought he actually meets every one of these criteria. Like, I have objective documentation of all of these things. And then I was faced with, okay, he's legally eligible, does that mean that I'm going to be comfortable providing for him? [Because] that doesn't mean I have to, just because he's eligible. I can pass, I can step away and say, “You're eligible, but I'm not comfortable.” But I thought, well, why wouldn't I? What exactly is holding me back? What exactly is making me stop? I felt bad. He's young, he's got young children. I mean, he’s got so much life in front of them. And then I, you know, I listened to his words, and I [thought], who am I to stand in his way? How unfair is that? And so actually I helped this man, I assisted him. It was a beautiful death, if you can say that, with close friends and family nearby. It was a beautiful, tragic circumstance. And I sleep fine at night. I know I did a good job with this family. I know I did my job. I know I did it diligently. I know that he met every legal criterion. And I know that to not do so I would have felt like I was standing in his way. That would have been harder for me, I think.

So, there are complex cases. Many of them will end up not being eligible, but some will. Some of my colleagues will feel compelled to do their duty and to help. Others will not. They'll step away, and that's okay. You need to be able to look at yourself in the mirror. There are patients I won't take, with more straightforward cases that remind me of a loved one or are exactly like an illness that a loved one had. I won't take those cases. I set my boundaries. It's important I do that and I stand by them and it keeps me healthy so I can help the other people who I can help. And my colleagues will have different boundaries. We need to respect this. You don't want to be involved in assisted dying at all, I totally respect that. One hundred percent respect that. The law respects it, I respect it. But my boundaries might be different than yours.

In 2016, no one knew what this would be like. How would it feel to do this work? In medicine, it is see one, do one, teach one. Only very few people stepped forward to see if they would be comfortable doing this work. We learned about it, we shared it with each other, and then we started to teach our colleagues what our experience was. We asked each other questions and learned, and then more people started to do the work. We had a community of people doing the work comfortably. Now in 2024, I expect we're going to have, again, a small slice of people who may step forward to do work with mental health patients, and the same thing will unfold in its own way.

I'm very grateful to you for speaking in such personal depth. It sounds like you sometimes deal with these harder cases. In general, what would you say is the hardest part about your job?

There's a few things. Number one, telling people that they're ineligible I think is probably for me . . . the hardest part of the job. These are people who've come to me asking to have help to end their life. [They are people] who believe they're suffering intolerably by definition, and who often have been marginalised by the system or not treated well by the system, or for whatever reason, have not been able to manage their situation. I can often validate their suffering because I see it, but that doesn't mean they're going to qualify for MAID. So telling someone that and explaining that nuance can be uncomfortable and can be awkward, and I know that it puts them at risk. They're deflated, and I need to make sure they're supported. I find that very difficult. So I think that's the hardest thing about my job.

I think it's also particularly hard in these newer, more complex cases that I've gotten involved with when I see patients who have been marginalised or not treated well. They've often not had the opportunity to access the resources that I know some other people have. Trying to find a way to offer them those resources can be extremely difficult, either because they are unwilling to accept that offer at this time because they're so fed up . . . and also, even just being able to refer them. While I'd like you to go see the pain clinic doctor, the waiting list is two years. Having that lack of timely resource availability is very frustrating when I see patients who I think might benefit from it.

Struggling with those resource allocation issues is very hard in this job, and I think will become [harder] as we enter trying to deal with mental health patients. Because accessing that care, it’s just deplorable. I mean, I used to defend the Canadian healthcare system, but it's currently broken.

The other things that are really hard in this job are when the system doesn't work . I wrote in my book [This Is Assisted Dying] about patients like a guy that I called Gordon. The law didn't allow for someone who made a request and [had been] found eligible and set a date—everything was set, and I show up and [he’d] become obtunded because of their pain medication, and he couldn't give consent at the time. I'm standing there in a room with a patient who I've promised to help, with the family who's begging me to help, and the law wouldn't have let me go forward. And that . . . was probably the hardest moment of my work. I would be breaking the law if I had gone ahead, and yet, who was I harming? I was causing more harm by not going ahead.

I want to end by returning to the need to say no to people. I was struck by something you said on a BBC Hardtalk interview, “If all the criteria were met and you’re eligible for MAID, it doesn't mean you're going to have an assisted death, or that you must, but that you may. That in itself is therapeutic.” I found that really poignant and I'm hoping that you might be able to elaborate on that and talk about that value of MAID.

Well, I love that you pulled that out. It is one of the greatest lessons I have learned in doing this work. In almost every patient that I see and assess when they've been through the process, when they've been through all the rigour, when I finally sit down and tell them that [they are eligible], I see a physical transformation in those patients in front of my eyes. Their shoulders relax, and there’s a slight grin on their face; it’s almost like an imperceptible nod. There's this understanding. It's sinking in that now they've been through that, and the choice is theirs. It's remarkable. Often, immediately, there is that expression of gratitude. I see, and I know objectively, this reduces suffering. They've come to me because they're suffering intolerably. And this conversation reduces their suffering. It's amazing. It's one of the most therapeutic things I can do. The conversation and the interaction [are] therapeutic in and of itself.

A significant number of those patients will then sit back and stop worrying about how they're going to die, what it's going to be like, and all their fears. They will immediately shift into how they're going to live the rest of their life. They go from thinking about dying to thinking about living. Some of them will extend their life because now that that element of suffering is reduced, they can actually live a little longer. And they can focus on making sure they see the people they want to see and saying the things they want to say. To say goodbye to people.

That shift from focusing on dying to focusing on living is so incredible to witness in patients. It's the reason that when I talk about assisted dying, I tell people that assisted dying is less about death than it is about how we wish to live our lives. It really is. People come to me because the things that brought meaning to their lives have gone. They can no longer do those things. They're no longer able to do those things. And so all those discussions are all about, well, what is it that brings joy? What is it that you can still have that brings joy? What does bring meaning? What has brought meaning? Those discussions are all about life, not about death.

It's remarkable how this work highlights what's important in life, as opposed to necessarily only what's important to death. Those conversations are absolutely objectively therapeutic. I think 80 percent of my job is done in that conversation alone, whether they go forward or not. I don't know another way to express it: it is profoundly meaningful work, to be in that position, to sit across from someone, and by talking to them know that you're reducing their suffering, and making them focus on life and what's important. I mean, wow, how meaningful. It's an incredible experience. It’s a privileged job.

I think that's the perfect note to end on. It's been great to be talking to you. So thank you so much for your time again.