Are 'green prescriptions' the no-pill solution for depression: recognising nature as a mental health service

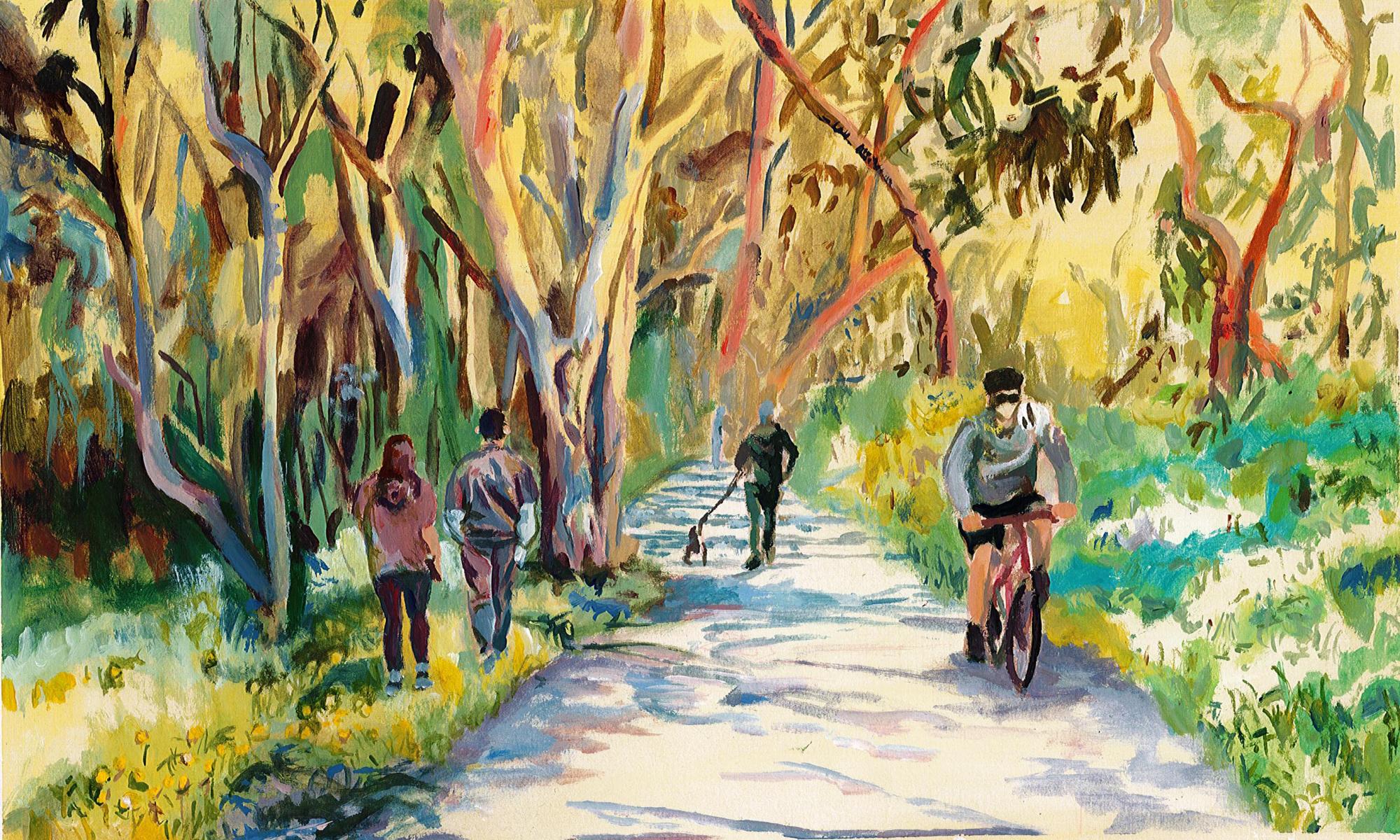

Improving one’s mental health is no walk in the park, but it is increasingly evident that strolling through green spaces does, in fact, have significant impacts on human physiology. The 'green prescription' is a mental health strategy that is gaining ground in healthcare systems worldwide, supporting people who are experiencing depression and anxiety with timetabled plans to intentionally boost their plantlife exposure.

As more of us are confined to built environments, modern health research is exploring the need for humans to engage more with nature. The COVID-19 pandemic exhibited the impacts of grey urban spaces on peoples’ mental health. Lockdowns provided researchers a wealth of case studies to observe the detrimental effects of insufficient nature exposure.

In 2020, cases of mental health disorders escalated in communities worldwide. One US study indicated a threefold increase in depressive symptom prevalence. And while a range of factors accounted for these observed statistics, interacting with the outdoors was certainly a stress mitigation tool. Merely having a window view of foliage during lockdowns in urban settings was enough to reduce levels of loneliness, depression and anxiety.

Contemporary understandings of nature meander through the positive health narratives that we see online. Social media performances of in-nature experiences—whether travel, hiking or weekend walks—connote wellness and relaxation. Digital platforms have hosted a wave of mental health conversations. Frequently, we are exposed to views of forests, mountains and beaches that spotlight the aesthetic, spiritual and cognitive benefits of these landscapes. Sometimes these superficial identity attachments are the driving factor behind our desire to spend time in nature. Superficial though it might be, this desire is a good thing.

Our ancestors appreciated that it was a good thing for humans to be in natural surroundings. ‘Shinrin-yoku’, the Japanese ritual of forest bathing, has been practised for generations. The holistic traditions in Indigenous cultures of living within, and in respect for, the natural world became traditions because they gave individuals mental and spiritual wellbeing benefits. Western structures of YouTube influencing and peer-reviewed academic literature have only recently caught on. Modern civilisation is being informed by past societies who knew something about how we best function as humans.

Science is affirming the effects of nature on our physical health too, from cardiovascular health to diabetes to heart disease. Is there some magic spell being cast in the sonnets of the city starlings, or do our bodies have some deep-rooted, automated response to the presence of soil and vegetation?

“We're fairly sure now that the major effect [of nature exposure] is simply one of encountering the organisms that we have evolved to require, because that is absolutely [an] essential part of our physiology,” states Graham A. Rook, a professor of medical microbiology at University College, London.

Graham Rook.jpg

Graham Rook is a professor of Medical Microbiology at University College London.

The human immune system has evolved in consistent interaction with microbiota. A firm believer that leaving garden vegetables unwashed will strengthen your immunity, Rook explains that the immune system plays an essential role in many of our internal systems. It has direct control of cortisol release. When the cortisol hormone is elevated, it initiates fight-or-flight stress processes within the body, leading to depressive symptoms.

Fundamentally, Rook argues, nature brings benefit to people experiencing depression and anxiety because their symptoms elevate with stress, and stress is reduced by being in a space that redirects our focus. Featherweight cognitive energy is expended when we must concentrate on where we place our feet on uneven, rocky earth. Reduced stimulation in these environments lets our inner conversations bloom. The question is, for how long does this peace of mind soothe our psychological distress? Is a long-term commitment to frequent nature visits the key?

An article in Scientific Reports, Health Benefits from Nature Experiences illustrates the linkages between nature and mental, physical and social health benefits this way.

Green Prescription in Practice

The green prescription was first implemented as part of a national health strategy under this explicit title in New Zealand, in the late 1990s when lack of exercise was acknowledged as a risk factor in depression management. Patients with mental or metabolic health issues could self-refer or be assisted by their GP into a three or four-month Green Prescription (GRx) programme to ensure that their physical activity met a minimum standard of 30 minutes, five or more times per week. Patients had no out-of-pocket expenses, and held frequent consultations with a GRx support person to help adapt the programme to their needs and lifestyle.

The GRx programme is ongoing. It values social cohesion and implements social cycling groups, cooking demonstrations, aqua sessions and group visits to national parks.

Since then, governments and organisations worldwide have promoted similar depression management solutions. Park Prescriptions or PaRx: A Prescription for Nature is a Canadian organisation that provides a toolkit to health practitioners, from physiologists to psychiatrists, to support their clients with nature intervention programmes. The PaRx programme uses a patient-centred approach that can be adapted into treatment plans alongside medication. The programme is straightforward: each week a minimum of two hours is to be spent in nature, in sessions of at least 20 minutes’ length, to maximise health benefits. PaRx believes this quantity of time is sufficient to lower cortisol levels, and for minds to declutter spiralling thought patterns into silence.

Launched in 2020 with the British Columbia Parks Foundation, PaRx has ambitions to grow in scale and innovate in technology. Soon they hope to launch an app allowing patients to track their outdoor hours. While digital tools and practitioner appointments can incentivise participants to meet their chosen nature-time targets, the effectiveness of having carefully measured outdoor activity has been questioned. One study argues that the pressure of following a programme undermines the participant's intrinsic motivation to head out to the park—converting a pleasure into a chore—and the expectation to commit to set goals may elevate anxiety, not alleviate it.

If green prescription programmes are to succeed, they also need to recognise the barriers that impede meaningful in-nature experiences. Nature experiences require time, energy and resources. For the busy, employed city dweller, it’s not always feasible to make the time commitments consistently. And what if an individual's local park doesn’t provide comfort, inclusion and facilities such as public bathrooms and water stations?

PaRx places accessibility at the forefront of its work

At the beginning of 2020, PaRx began using a new strategy to connect people with depression and anxiety to Canada’s pristine coastal and forest landscapes. In a collaboration with Parks Canada, Free Parks Discovery Passes are provided to programme clients, giving them year-long admission to 80 parks, historic sites and marine areas throughout the country. PaRx founder, Dr Melissa Lem, says she has already observed positive implications for PaRx patients.

Dr Melissa Lem.jpg

Dr Melissa Lem is a family physician and founder and director of PaRx.

“[One] patient broke down into tears when her prescriber told her she was prescribing her a park pass, because of the meaningful difference it would make to her ability to access nature.”

But national parks don’t sit on everyone's doorsteps and Lem has ambitions to work with transit organisations to support inner-city residents and new immigrants to access these national parks.

Lack of accessibility to nature tests the viability of green prescriptions, and unequal access to urban green spaces became pronounced during the lockdowns of 2020. Many Global North countries observed higher utilisation of urban green spaces, which may be no surprise as white collar workers gained the freedom to schedule park exercise sessions into their working day.

However, the opposite trend was observed in Latin American countries. Nature interventions are out of reach for many residents of Mexico City, where a majority of neighbourhoods do not have green spaces within 300 metres (a metric set by the World Health Organisation to define accessibility to urban green spaces). And perhaps it’s no surprise that those with least access—poorer neighbourhoods, women, people with disabilities and ethnic minorities—were least active in urban green spaces during COVID lockdowns and had higher rates of depressive symptoms.

Geography PhD candidate of the University of Melbourne, Carolina Mayen Huerta, argues that besides proximity, Mexico City’s urban infrastructure failed to connect key demographic groups with nature. In her research into the intersectionality of urban green spaces and health in Mexico City over the past years, Carolina has noticed inadequate socio-environmental consideration of women in particular.

While the pandemic imposed additional stressors of increased household responsibilities, violence and unemployment; women felt too discouraged to utilise parks as coping mechanisms. Urban green spaces in poorer neighbourhoods lacked cleanliness, security, facilities for children and aesthetic values.

“It is imperative to recognise that for women, the concept[s] of quality and safety are intertwined and are determining factors for the use of spaces,” Carolina argues. This goes for not only the urban green spaces themselves, but also for the routes taken to reach a green space from home.

One woman in Carolina’s research survey commented, “The road leading to the park is ugly; I do not feel safe walking there.”

Expanding the use of green prescriptions as a cost-effective public health solution

Utilising natural landscapes for improving anxiety and depression needs to start with city design and planning that considers everyone, Carolina argues. “It is necessary to conceptualise the city from various perspectives and not only from the male perspective . . . Incorporating a gendered outlook into the development of green spaces, and urban planning in general, is critical so that women increase their urban green space use and feel comfortable and safe while using these spaces.”

Carolina Mayen Huerta.jpg

Carolina Mayen Huerta is Geography PhD candidate of the University of Melbourne.

Achievable policy steps would include investing in street lighting, road maintenance, garbage collection and security infrastructure. Advocating for a vision of socially cohesive neighbourhoods would ease people's perception of their vulnerability. Active local participation in project planning would prioritise infrastructure that responds to local needs. The presence of parks with the resources and visual qualities to promote fitness and outdoor activity would encourage longer, more meaningful nature visits.

Nature's improvement of physical and mental health can also save on health service budgets. A 2016 study found that 30 minutes or more per week spent in nature leads to a seven to nine percent reduction of depression and high blood pressure. The benefits are also financial: societal costs from depression for the employed Australian population are estimated at 12.6 billion AUD per year.

Various metrics evaluate the effectiveness of green prescriptions differently—from blood pressure measurements to questionnaires about happiness—so positive health outcomes have not been quantified as crisply as dollars. You could walk down many paths investigating the importance of frequency and duration of nature visits, as well as the biodiversity and aesthetics of public green spaces. Perhaps there is no ‘copy and paste’ solution when it comes to prescribing individuals these programmes, because we are all unique.

When the noise and pressures of society are applying a stress that is significantly impacting your daily mood, try paring it back. The simplicity of watching light patterns travel across foliage while breathing in the clean air of nature may have more value for your mental health than you think.